From 1540 to 1542, decades before European colonies were established on the Atlantic side of the Americas, the Spanish conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado led an expedition from Mexico, where he was governor of New Galicia, north through what is now Arizona, New Mexico, and across the plains of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. The expedition’s search for the fabled “Seven Cities of Gold” proved to be a failure, and Coronado returned to Mexico in disgrace.

Scan the QR code above or click here to view the route on REVER

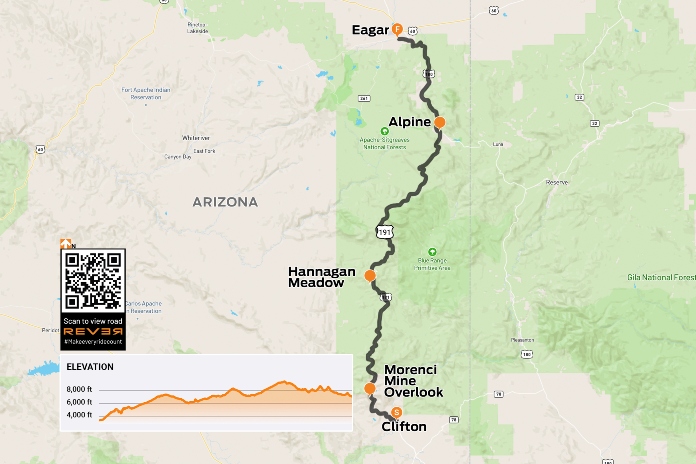

Coronado’s path through Arizona went due north through the eastern part of the state, climbing into the White Mountains that are part of the vast Colorado Plateau. His expedition followed Native American footpaths, which later became horse paths and wagon trails used by hunters, outlaws, pioneers, and prospectors. Today, the route is largely paved, and 120 miles of it are preserved as the Coronado Trail National Scenic Byway, twisting and turning from the mining town of Clifton in the south to the high-desert town of Eagar in the north.

My faithful riding companion Eric Birns and I arrived in Arizona from the east, having spent the previous week riding from California to Texas to witness the April 2024 total solar eclipse, then exploring Texas’ Hill Country and the Big Bend region. We entered Arizona on State Route 78, winding our way through the southern end of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest and cresting a craggy ridge at 6,102-foot Needle’s Eye, then descending 2,500 feet over the next 13 miles on a freshly paved dream coaster to Three Way, where U.S. Route 191 and State Routes 75 and 78 meet.

U.S. 191, which runs from the Mexican border to the Utah state line and includes the Coronado Trail, was once designated U.S. Route 666 (the sixth spur off U.S. 66) and earned the nickname “Devil’s Highway.” Pushback from religious folks, not to mention a propensity for knuckleheads to steal the 666 highway signs, led officials to renumber it as 191 (yawn).

Eric and I overnighted in Safford at a cheapo Motel 6 within walking distance of JD’s Grill House, where we refreshed our road-weary old bodies with frosty ales and high-calorie pub grub. Up and at ’em early the next day, fortified with lousy coffee and stale protein bars, we fired up our big Harley Glides and made our way back to U.S. 191.

We stopped to take in the sights in Clifton, a copper mining town founded in the 1870s that’s located at the confluence of the San Francisco River and Chase Creek. Clifton’s historic district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and includes dozens of buildings built in the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Riding north out of town, the road climbs through two sweeping hairpin turns and turnoffs for Morenci, Clifton’s sister city, as it enters an industrial area. At a confusing junction, we mistakenly turned onto an access road for an ore-processing facility.

After realizing we weren’t in Kansas anymore, we returned to the main road and soon entered the Morenci Mine, one of the largest open-pit copper mines in North America. Its scale boggles the mind. There’s an overlook off U.S. 191 where you can turn around 360 degrees and not see a single bit of earth that has not be graded, reshaped, dug, or moved. With reddish dirt as far as the eye can see, it looks like a Mars terraforming project out of a sci-fi movie. Operating around the clock, the mine processes 700,000 tons of rock per day and upwards of 840 million pounds of copper per year.

We watched dozens of ore-hauling dump trucks that, from our vantage point, looked like Matchbox vehicles. In reality, each Caterpillar 793D truck is 42 feet long, 21 feet high (each tire is 11 feet in diameter and weighs over 8,000 lb), weighs 350,000 lb when empty, has a payload of 480,000 lb, and is powered by a 2,000-hp, 16-cylinder diesel.

We were at once impressed by such an enormous human achievement and horrified by the gigantic scar on the Earth.

Riding farther north, the mining hellscape was soon replaced by enchanted mountain scenery with rugged pink rock formations and dark green trees. The contrast was jarring, and the 1st-gear hairpins demanded our attention. It was a perfect spring day, crisp and clear, nary a cloud blemishing the blue heavens.

It was a Saturday in mid-April, our eighth day on the road, and Eric and I had fallen into a comfortable rhythm. Though I had read about the Coronado Trail several times in the pages of this magazine, neither of us had ridden it before. We were like sponges, absorbing the sights, sensations, and sensational curves at a rapid rate.

We entered a burn area and rode above the snow line as we approached 8,783-foot Rose Peak. Ready for a break, we stopped along the roadside, and Eric opened up his traveling snack bar: trail mix, candy, jerky, energy drinks. We were both in awe of the Coronado Trail and the majestic scenery. Eric is always generous with his caloric bounty, but what I appreciate even more is an endearing quality that he reveals at times like these. Inspired by the moment, Eric will recite poetry – Shakespeare, Keats, and others – and breathe even more life into the beauty that surrounds us. Life and shared experiences are precious, so why not elevate them even higher?

As U.S. 191 works its way north, its character constantly changes, giving riders a full experience. Tight curves, sweeping curves, grades that rise and fall, straight and flat sections that provide relief, vistas that go on for miles or are hemmed in by trees and rock walls – it’s all here.

Since leaving the Morenci Mine, we had seen no development along the Coronado Trail. A few campgrounds and some trailhead signs, but that was it. Cell reception is blessedly nonexistent. Our next stop was Hannagan Meadow, which was covered in a blanket of snow. The Hannagan Meadow Lodge, located 9,000 feet above sea level in the middle of the Blue Range Primitive Area, is the only bit of civilization for miles. Built in 1926, it offers accommodation in the lodge or cabins, and the restaurant serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner. We were just passing through, but Arizona-based Contributing Editor Tim Kessel gives the lodge an enthusiastic endorsement.

The next 23 miles to Alpine were a pleasant, gradual descent along graceful curves. From Alpine, you can complete a 211-mile Coronado Trail loop by riding east on U.S. Route 180 into New Mexico and then slithering like a rattlesnake south to SR-78 for the return to Arizona.

At the Tackle Shop, we watered our horses and scuffed our boots on the store’s worn wooden floor in search of provisions. If you’re an angler, this is your place. I bought a sheet of Arizona Jack’s Super Giga beef jerky, which had “AZJ” branded on it and tasted like peppered shoe leather.

The final 27 miles of the Coronado Trail from Alpine to Eagar is a mellow cruise through the national forest with fewer curves and less dramatic scenery, concluding our ride on the scenic byway. This is a road I can’t imagine ever growing tired of, especially since it’s remote enough that it probably never sees much traffic. And for the adventure-minded, there are unpaved forest roads off U.S. 191 that will take you to primitive campsites along the Blue and Black rivers.

We ended our long riding day more than 200 miles west of Eagar in Clarkdale, at the home of Tim Kessel and his delightful wife, Cheryl, enjoying a dram of sippin’ whiskey. Over dinner at a local restaurant, we shared tales of our travels, reliving the highlights all over again. Ride to live, live to ride.

See all of Rider’s touring stories here.

Coronado Trail Motorcycle Ride Resources

This Article First Appeared At ridermagazine.com