Making his case for national 55 mph speed limits in the summertime of 1988, Senator Frank Lautenberg brought out a well-worn highway safety slogan: “The statistics show that speed kills.” Lots of his colleagues, still working within the long shadow of the sixties counterculture, could have situated that grave warning in congressional testimony about flower-children in Haight warning one another off amphetamines: “Speed Kills!” And when you wandered into the proper record store in Chicago within the early 90’s, you’ll have seen a music fanzine promising drag racing, record reviews, and more: “SPEED KILLS.”

For the uninitiated: a music fanzine was a form of connective tissue. An area zine (pronounced “zeen”, like maga-zine) could inform you about recent shows in your area, or present an interview with musicians who lived or worked nearby. Many published reviews for recently released music, with mailing addresses for independent labels and distributors. Every little thing wasn’t analog, obviously. Usenet groups discussed music way back to the 1980’s, and by the late 1990’s an mp3 could travel well enough on 56 kb/s for Napster to scare the RIAA. But to truly get music into your hands, and to listen to it at its full texture, you might fastidiously copy an indie label’s mailing address out of a fanzine, stuff a couple of bucks into an envelope, and wait by the mailbox. In the event you liked what you heard, and kept following that thread, massive ecosystems of D.I.Y. music opened as much as you.

While some music fanzines took a caustic approach, many emerged out of irrepressible enthusiasm for his or her scene or their subject. The more present, immediate, you might make it for the reader, the more they might grab onto and understand why you’re keen on this thing a lot that you would be able to’t hold it back. That is the form of thing people say about automobile culture: bring someone with you to a race; bring them to a automobile show you’re captivated with; bring them a souvenir a minimum of, in order that they can touch a chunk of it. Connect it one way or the other to the things that they’re already concerned about. Make your enthusiasm tangible. Within the case of the fanzine, which means type and cut and glue your individual zine for print, and and use it tell anyone who will listen: “I like these items! These things will change yr life!”

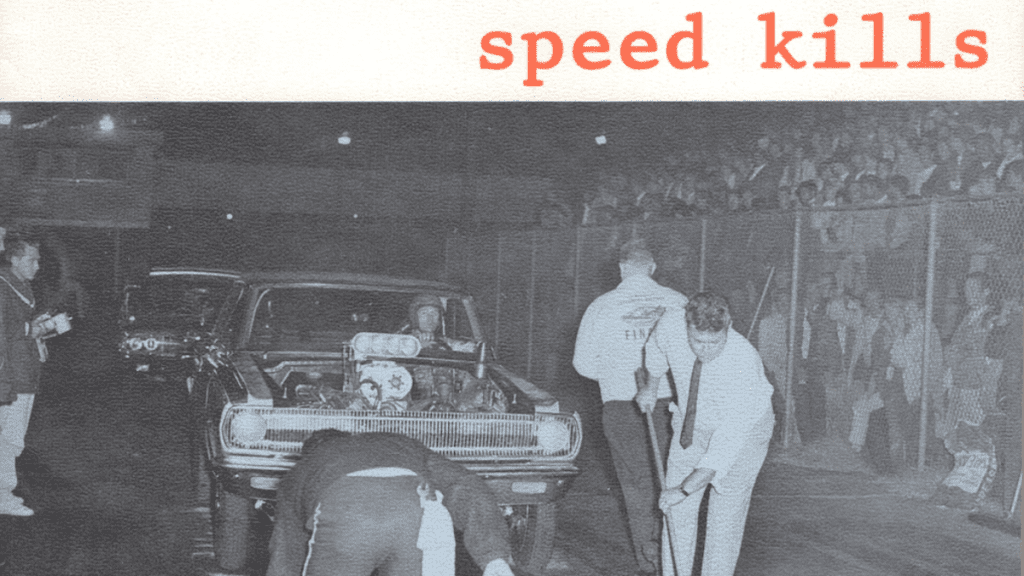

Chicago music fanzine Speed Kills, edited by Scott Rutherford, made its particular “stuff” clear when its first issue went to print in 1991. The hand-screened cover shows a cartoon skeleton in a dragster, and guarantees two interviews (Seaweed and Gas Huffer) plus “DRAG RACING! 60’S STYLE,” and “LOTSA REVIEWS!” to discover itself as a music zine.

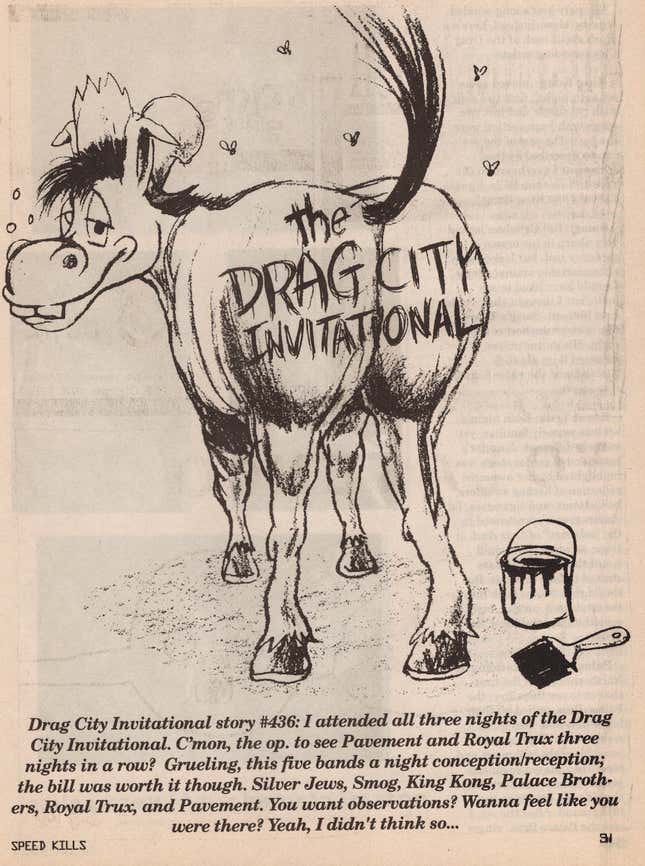

The music reviews in Speed Kills #1 are standard fare, pulling from the catalogs of Sub Pop, Merge, K, SST, and Drag City, amongst others. Reviews for Nirvana, Pavement, Smog, and Superchunk run across Speed Kills’ newsprint pages, next to straightforward indie label ad-buys (and, in somewhat Speed Kills twist, vintage ads for auto parts.) It’s not all tonal, structured stuff: two Trance Syndicate releases are really helpful within the “gtr. fuzz tape collage damage” of Pain Teens and the “unnervingly demonic” tape loops of Crust. But a curious reader skipping the remainder of the zine to examine the reviews could have their eyes already in motion, past Harriet Records’ Wimp Factor 14 and Chicago locals Wreck, into the following page. And across the page gutters from the last reviews, continued from page 21, is an interview talking about Ford and oil springs as an alternative. Flipping back to page 21, we discover the promised feature on drag racing.

The interview is with Larry Ammons, introduced here as “one among Cleveland’s local legends!” Rutherford prompts and follows along, as Ammons talks about street racing in Cleveland, driving to Livonia to ask Ford engineers questions, and the Detroit Autorama. He tells anecdotes and talks concerning the cars he drove within the sixties, he rattles off names and specs. What’s striking is the detail kept within the interview. In preparing it for print, Rutherford left the main points in: as Ammons discusses the innovations he put into his Boss 429, he talks about journals, bearing surface, a model of carburetor. For somebody picking up Speed Kills for the music reviews, who’s never thought twice about what’s under a automobile hood besides the really helpful maintenance intervals, that is all alien. However the parties involved speak about it with total fluency, without pausing to elucidate. The curious reader flips to the music interviews for something grounding. What’s the cope with Gas Huffer? Well, in boxes throughout their Q&A, you’ll find quick, readable, mildly sarcastic instructions on methods to replace the rear primary seal on a crankshaft.

This was the connective tissue that Speed Kills provided: you’re already here to see what the curious, creative, weird people of the world can do after they get their hands on music; wait until you see what they will do with cars.

The received wisdom about subcultures is that this might never work. Surely, when you like drag racing, you’re blasting “I Can’t Drive 55″ out of your automobile stereo, not reviewing records from the label that put out Double Nickels On The Dime. These are decades-old Kinds of Guy locked in ideological combat. But there’s a useful frame for this in issue #6’s feature on Hot Rods From Hell. Speed Kills correspondent Wealthy Dana describes the group’s purpose: “To hunt down recent life in a racing style mostly missed because the big bucks of corporate-sponsored funny cars and top fuelers eclipsed it within the early seventies.” HRFH organizer Scott Jezak concurs, and Dana quotes him as saying: “Funny cars now are mainly tools to get down the track… I like to look at them run, but drag racing today lacks character and individuality.”

In 1994, John Force and capital-F capital-C Funny Automotive may not have been NASCAR or F1, but for these drag enthusiasts closer to their hobby’s margins, all the pieces is relative. Is that this so different from how D.I.Y. labels hand-dubbing cassettes checked out Sub Pop, even before their Warner takeover? Sub Pop still oversaw great records after 1995; you continue to love to look at Funny Cars run. But when you want something tactile, something accessible, you may have to get lower to the bottom.

In that very same spirit of the Hot Rods From Hell, in search of out the visible hand of the opposite human, Speed Kills faithfully devotes review space to small labels. This isn’t to say that its top-fuel brand ever lets up for long. The attention catches on bands with automotive-themed names amongst reviews: Cheater Slicks, Fastbacks, Alcohol Funnycar, Voodoo Gearshift, Crain. But space is made for music that only exists because the painstaking work of individuals with day jobs and tape recorders. Speed Kills often features short but glowing reviews for Refrigerator, brothers Dennis and Allen Callaci of Shrimper Records. Shrimper, best often called the primary home of prolific rockers the Mountain Goats, relies in Claremont, CA; ten miles from the old NHRA headquarters, and thirty from Riverside International Raceway. A Speed Kills review of a neighboring label’s split single demands: “What the hell is occurring in Claremont?” What, indeed, was occurring just north of the Pomona Raceway? Speed Kills gave up attempting to answer that on a minimum of one occasion. Sidestepping an actual review of the hypnotic, churning rock of Shrimper alumni Halo, the SK review section rambled as an alternative concerning the ‘68 Chevy Impala 4-door on their CD’s cover.

Throughout its run, the staff of Speed Kills negotiated its two primary sensations—speed and sound—this manner, one turning into the opposite. An interview with 1978 NHRA Champion Kenny Cook reveals mid-way that Cook’s brother Jon plays guitar with Louisville rock band Crain (friends of the magazine), and that Kenny fixes the band’s tour van. When Speed Kills sent out Issue #5’s “Fave Automotive Survey” questionnaire, it drew responses not only from John Pearley Huffman (formerly of Automotive Craft), but from mischief-maker Nardwuar, Merge Records’ own Laura Ballance, and Steve Albini. An interview with musician Eric Lunde gets loose halfway through, and leaves music behind for an extended discussion concerning the aesthetics of collision, and the sacredness of Figure 8 crashes.

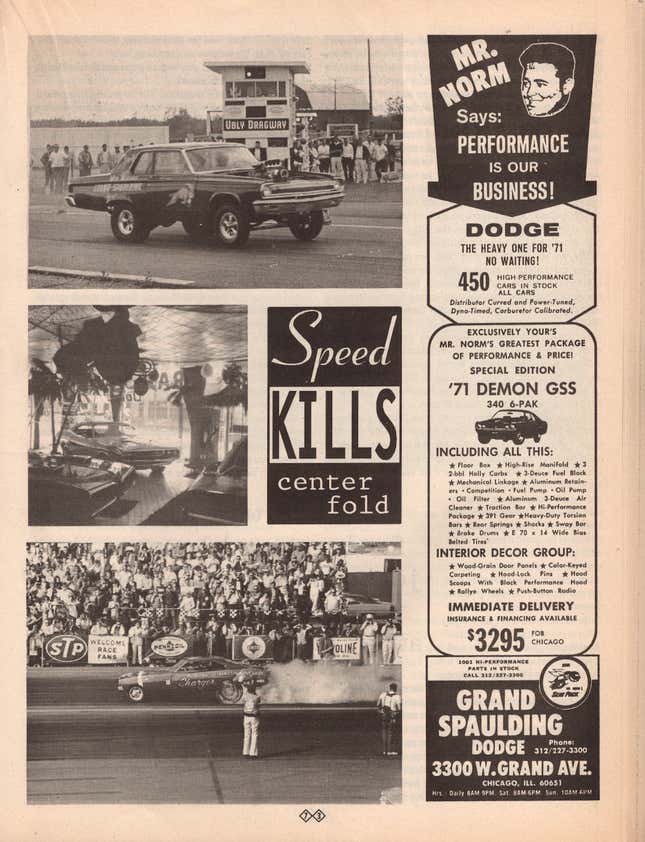

In one among its strictly automotive features, Speed Kills opted for a distinct form of zine scene report during its run: interviewing Chicago’s own Norm “Mr. Norm” Kraus, legend of Grand-Spaulding Dodge and drag racing innovator, at length. The interview is introduced “delivered to you by the Speed Kills Historical Society!” in jest, nevertheless it gets quite literally all the way down to nuts and bolts. You may almost hear the enjoyment, reading Norm Kraus’s answers concerning the sorts of custom work they did for patrons, making their cars faster: “We discovered that the 383 bearings worked higher than the Hemi bearings!” Asked about performance and weight, he goes on at length concerning the ‘67 Dart, concerning the manifold being too near the steering coupling in early tests. He talks about how he ended up in racing, and slides into long vigorous anecdotes, dutifully transcribed and giving a sense of constant easy motion. His sense of where things were on the cars and the way each part he altered would make things faster, who he worked with and where he was, his tactile feeling, all comes through clear and sharp. The “Mr. Norm” interview runs long, split in half and pushed to the back of the sixth issue, to carry all of those details. The interview is original work, helpful work, and might’t be replicated or re-done. Norm Kraus passed away in 2021.

Last summer I used to be mailed a heavy cardboard box. Inside was a stack of music fanzines, scattered issues, all from roughly the identical early 90’s period and with some interesting niches. The Tim Alborn/Harriet Records zine Incite! interviewed librarian-musicians in its twenty eighth issue, asking whether or not they preferred Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress systems. One other zine, Escargot (eds. Jeanne McKinney, Kathleen Billus, and Windy Chien) had detailed details about getting online in 1995, from picking an ISP to netiquette to UNIX commands. Issues #5, #6, and #7 of Speed Kills got here to me amongst these other enthusiasms, a form gesture from a friend sending me research material. Digging through the reviews, wandering back through the features, I got the gist of Speed Kills and set it aside to maintain sifting through all the fabric available. But I kept coming back to the sixth issue, which had originally been mailed out with a Superchunk single. I hadn’t heard of Speed Kills, but I wondered if any of my Superchunk devotee friends had seen the name, or had a duplicate.

The sixth issue of Speed Kills is less complicated to seek out than the early issues. Due to Superchunk single, an item with reasonable demand and value for collectors, copies of issue #6 usually tend to have been bought, bagged, stored, indexed, together with the 7″. There’s a really real possibility that the interview with Norm Kraus, in all its great energy, all its detail, will survive for a drag racing enthusiast further down the road to check and luxuriate in, well beyond the bounds it might need otherwise.

And on the extent of sheer enthusiasm: I personally hadn’t given drag racing or hot rodding much thought, before digging into these. Now my ears perk up after I hear news concerning the NHRA, or after I see old problems with Automotive Craft by the antique store rows of Road & Track. Scott Rutherford and the remainder of the team who made Speed Kills poured their effort, their time, and their love for their very own area of interest of automobile culture into the zine, and that reached me still in 2024. It brought me along, and it told me the one thing I needed to know: they loved these items. These things could change yr life.

This Article First Appeared At jalopnik.com