Japan’s vast road network boasts 1.2 million kilometres of tarmac across its sprawling landscape.

That may sound like so much, however it manages some 82 million vehicles in a few of the world’s most densely populated cities every day. As a rustic, it ought to be at a perpetual standstill. Yet, ever for the reason that Nineteen Fifties, the Japanese have held a tiny little ace up their sleeves…

Kei-jidõsha, or ‘kei automobile’ because it’s more commonly known, refers back to the smallest category of motorized vehicles permitted to drive on Japanese roads and highways. For a long time, the kei class has produced a few of the most unusual-shaped vehicles anywhere on the planet, powered by bike-sized engines with tyres that wouldn’t look misplaced on a wheelbarrow. In an automotive landscape more bloated and chubby than ever, the Japanese kei automobile appears to be the cheat code required to beat the system.

This phenomenon first entered service back in 1949, after the Second World War. Japan needed to mobilise its country again, but limited resources and a weakened economy meant traditional commuter vehicles were out of reach for most individuals. Enter the brand new ‘light vehicle’ class, initially limited to a 150cc four-stroke engine (or 100cc two-stroke), followed by a bigger 360cc limit within the mid-Nineteen Fifties. It’d take until 1958 for the primary mainstream kei automobile to take off – Subaru’s 360 – which boasted seating for 4 while measuring under ten feet long.

By the Nineties, kei class engine capability was raised to 660cc, and with manufacturers embarking on forced induction to spice up power and efficiency, it soon yielded a few of the most iconic models thus far, including the Suzuki Cappuccino, Autozam AZ-1, and Honda Beat. There wasn’t an official limit on power, but a gentleman’s agreement capped it at 63hp. Dimensions, nevertheless, have remained the identical since 1998 – not than 3.4m, no wider than 1.48m, and no taller than 2.0m. Kei cars don’t must adhere to the identical safety standards as non-kei cars, which is why you rarely see them sold officially outside of Japan. Not because they’re inherently dangerous, but you’d assume the Euro NCAP team wouldn’t look too favourably at your shins forming a part of a front-end crumple test.

Such is their popularity that kei cars account for greater than a 3rd of all vehicle sales in Japan. But rewind to those adolescence before their popularity boomed, and there was one other vehicle trend emerging that made even the smallest kei cars feel like a Hummer as compared. A category that didn’t even require a driving license to make use of since the Nineteen Seventies would mark the launch of the even wackier world of Japanese microcars. What’s more, the driving force behind them was a manufacturer you’ll already be conversant in in terms of constructing obscure, alien-like vehicles. Take a bow, Mitsuoka Motor.

Before Mitsuoka spent their days transforming K11 Micras into AI-generated Jaguar Mark IIs, its business centred around importing and servicing European cars for patrons across Japan. Founder Susumu Mitsuoka all the time dreamt of making his own vehicles, however it wasn’t until the late ’70s that he was capable of achieve this. When a customer brought their Italian microcar in for repairs – a Casalini Sulky – Mitsuoka-san was left frustrated that he couldn’t find the parts required to repair it. Reasonably than hand over, Mitsuoka-san adopted the optimistic Speedhunters attitude and declared how hard can or not it’s? Several years later, in 1982, Mitsuoka’s first complete automobile was born – the BUBU Shuttle-50.

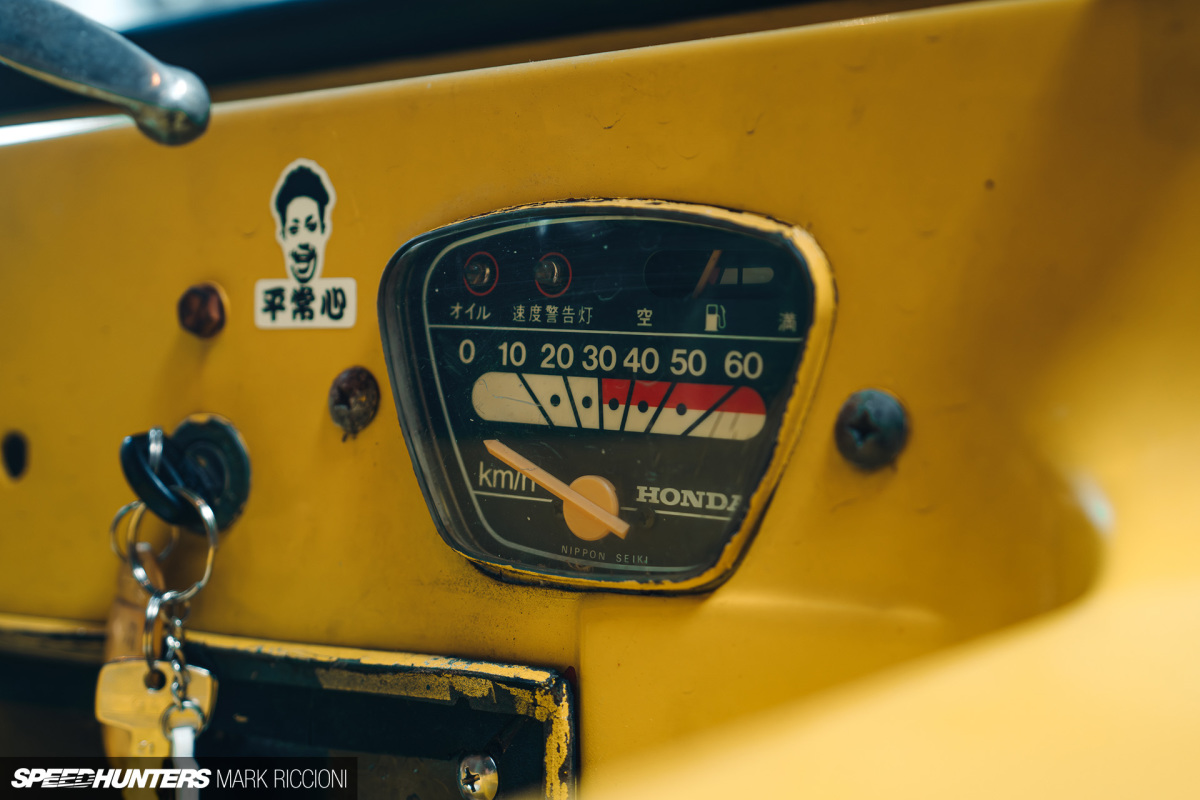

To call the BUBU Shuttle-50 a automobile by modern standards is perhaps pushing it, though it does have doors, wing mirrors, and a windscreen. Its engine measured just 50cc, driving a single wheel on the rear, with two further wheels up front doing the steering. But this wasn’t Mitsuoka being weird for the sake of it; its goal was to mobilise all Japanese people. Due to its 50cc engine with steering, throttle, and braking controlled by handlebars, the BUBU Shuttle-50 only needed a moped license to be legally driven on the road. What’s more, its rear-opening door – complete with fold-out ramps – allowed it to be utilized by those with disabilities, because of the hand controls. It could even fit through a doorway, meaning you didn’t need the luxurious of a garage or off-street parking to store it.

The BUBU Shuttle-50 was quickly joined by the BUBU 501 in the identical 12 months, a smaller, sleeker model that also only featured a 50cc engine and three wheels, albeit with the addition of a steering wheel. Three years later, the BUBU 505-C joined the range, which mimicked a quarter-scale Morgan Roadster. Mitsuoka shifted into full-size vehicles from the late Nineteen Eighties onwards, but their microcar vision remained a part of their model range as much as 2007.

Every vehicle – despite looking obscure even by Mitsuoka standards – served an important role that even kei cars couldn’t fulfil. Not only were they much more convenient for navigating Japan’s (often) tiny roads, but a moped license was considerably cheaper to acquire than the equivalent automobile one. While sales were never really booming, the microcar market went from strength to strength right until the late ’80s when a regulation change would all but seal their fate. Other than safety now being quite essential, microcars would now require a full driving license to operate, dramatically slashing their appeal.

Nevertheless, a long time later, there’s a minimum of one man in Japan who has made it his life’s mission to hold on the legacy of this bizarre era of Japanese motoring: Wakayama-based Kaoru Hasegawa.

“I got my first microcar nearly 30 years ago,” Hasegawa-san proudly states. “I actually have all the time enjoyed small vehicles, and I used to be given my first microcar. It had been abandoned within the corner of a automobile shop out within the countryside, so I hung out restoring it and began driving it around. It was a lot fun, and the response from other people was amazing. I knew I wanted one other microcar, so I began looking around and researching their history.”

Despite hundreds of microcars being sold across Japan, tracking down a superb, working model is becoming as difficult as unearthing rare supercars – mainly because most individuals bought microcars for quick and straightforward transport fairly than something to cherish and collect. For Hasegawa-san, he knows that is half the appeal, too. A lot of us are conversant in the BMW Isetta and Peel P50 – each sold throughout Europe in much larger numbers – but what makes the Japanese models much more desirable is how much smaller and rarer they were as compared. Hasegawa-san’s collection now features greater than 10 different models, and despite being three a long time deep into his obsession, he’s still looking out for more.

“Once they were latest, microcars might be driven with a moped license, so that they sold thoroughly,” he adds. “Especially amongst housewives, as that they had been designed to permit people to maneuver quickly with luggage or shopping in all weather conditions. They were less expensive than a automobile and might be stored in a traditional house easily. But when the brand new law was passed, meaning that owners needed a driving license to run them, the sales stopped and dealers turned their attention towards kei cars as an alternative.”

Hasegawa-san is greater than only a collector of those oddities. For years, he’s shared his love for them across social media, and it wasn’t long before he was being inundated with messages from intrigued automobile fans attempting to decipher what they were taking a look at or likeminded microcar enthusiasts that – in lots of cases – assumed the early Mitsuoka BUBU models would never be seen again. Hasegawa-san’s collection expands beyond Japanese cars, nevertheless. Two of his cherished models include the Italian Cassalini Sulky and All Automotive Snuggy Charly, and yes, those are the actual names. Given the worldwide interest his humble little collection had gained, Hasegawa-san decided it was time to create an actual museum for his microcars. That may sound like an unlimited and expensive project until you realise that each one of his collection matches comfortably in a daily downstairs garage.

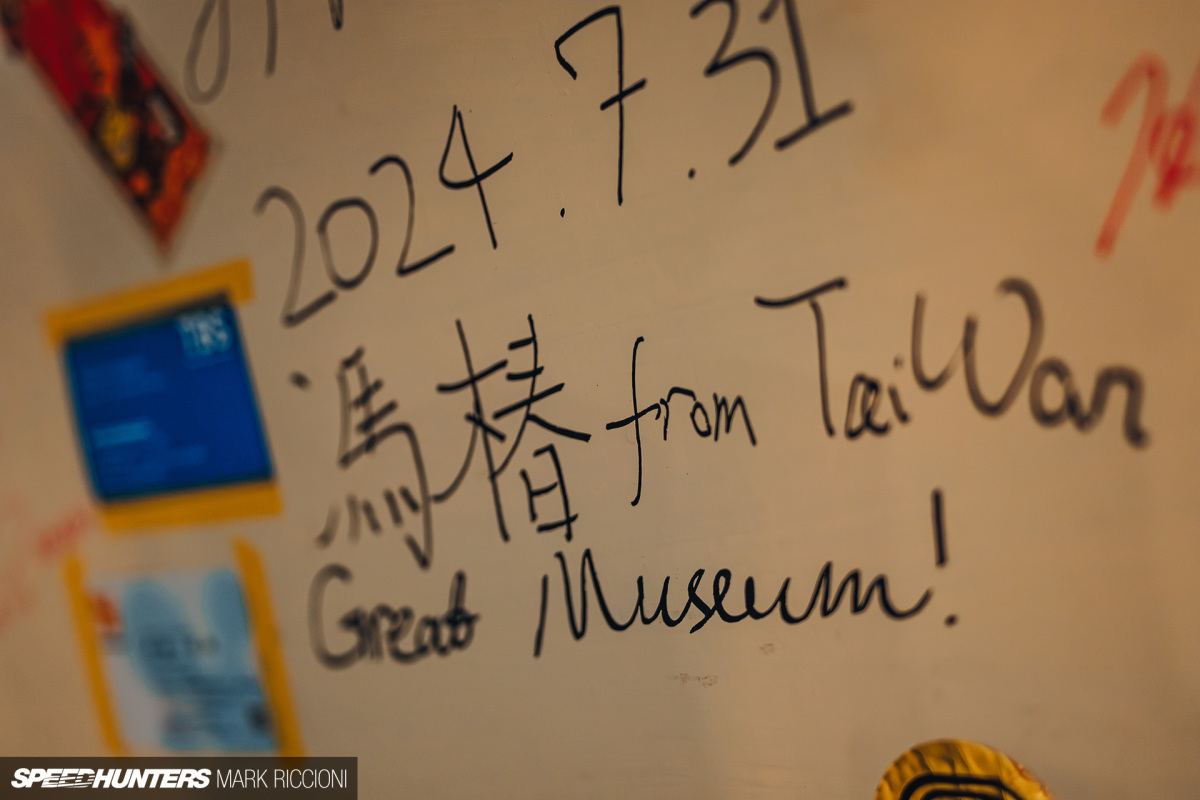

“I created the WAZUKA Microcar Museum due to messages I kept receiving on social media from people wanting to see the true things,” Hasegawa-san adds. “There are a lot of automobile museums in Japan, but there isn’t any museum anywhere that specialises in microcars! So, I assumed I might make one myself. All the cars on display are in good, original condition while also being the models produced within the least numbers. I actually have travelled all across Japan to seek out them, and the chums gathered here with me were all enthusiasts met along the best way.”

Reasonably fittingly, the WAZUKA Microcar Museum is situated on a tiny street, crammed right into a tiny terraced house with the upstairs living quarters suffering from tiny memorabilia. It is totally unassuming on the surface, but its charm is just matched by the quirky vehicles it houses behind the wooden-slatted garage door.

Despite this, Hasegawa-san recurrently hosts microcar gatherings by inviting friends and enthusiasts including Sinchirou Kubo and his Morgan-like BUBU 505C, Kai Kuramochi who has stretched his Casalini Sulky to hold passengers, and Takayuki Teramura whose Casalini Sulky is slammed so low to the bottom it’ll beach on any speed bump if he doesn’t approach it fast enough.

These 4 owners and their cars will shut down any street with intrigue and crooked necks greater than any fire-spitting Lamborghini could dream of. All 4 will slot in a single 7-Eleven parking bay, and, providing you go nowhere near a highway, their top speeds can vary between 65km/h and 85km/h depending on wind direction and road gradient. They’re unlike the rest you’ll see on the roads, and their intrigue captivates nearly all ages and generation.

“We don’t get many tourists down here!”Hasegawa-san laughs, which is unsurprising given it’s a seven-hour drive from Tokyo and two hours south of Osaka. “But my goal is to inform everyone in regards to the museum and show them the history of the microcar. I’m all the time searching for more cars so as to add – it’s half the fun with microcars because they often find yourself in probably the most obscure and weird places. So to bring as many together as possible – and keep them in good usable condition – is a dream for me that I’ll proceed to live out so long as I can.”

Kaoru Hasegawa’s WAZUKA Microcar Museum is situated within the Kainan region of Wakayama, Japan. To rearrange a visit, you may message him at @kaoru.bubu on Instagram.

Mark Riccioni

Instagram: mark_scenemedia

Twitter: markriccioni

mark@speedhunters.com

More stories from Japan on Speedhunters

This Article First Appeared At www.speedhunters.com