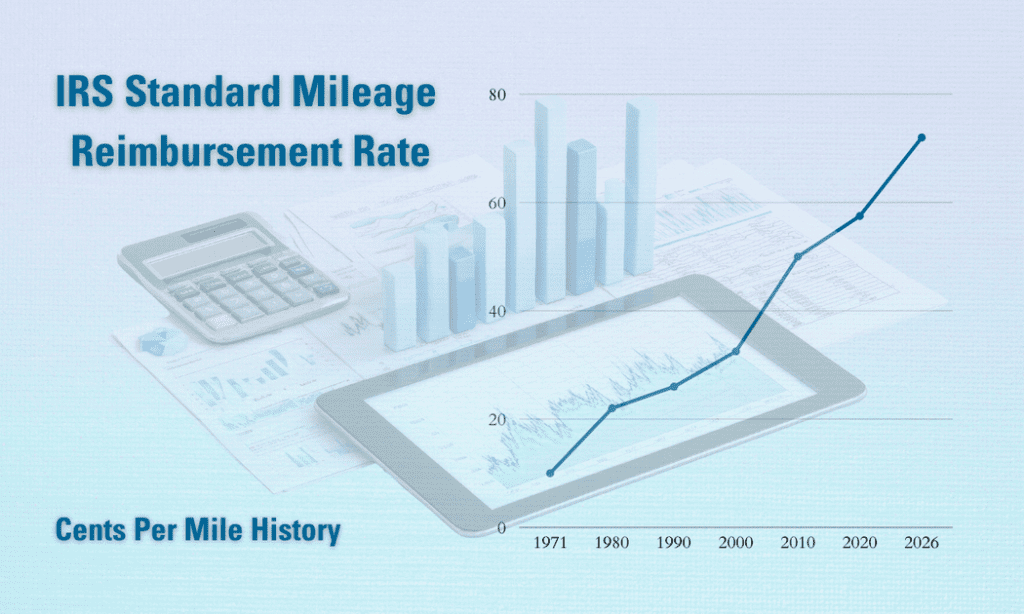

The IRS standard mileage rate remained remarkably stable through the Nineteen Eighties and Nineteen Nineties, but within the 2019-2023 period alone, it saw a 9.5-cent swing driven by pandemic disruptions, supply chain chaos, and record inflation.

Ah, the IRS standard mileage reimbursement rate. From 1980 to 1989, the speed only fluctuated by 2 cents! (And so they thought inflation was bad back then?)

Flashforward to 2026: The speed has climbed to 72 cents per mile, an almost 30% increase from 56 cents in 2021. It’s no use to pine for the great ol’ days, because they’re not coming back.

The recent spike reflects rapidly rising vehicle ownership costs that fleet managers increasingly feel across each company-owned and employee-driven vehicles.

But using the IRS rate as a default reimbursement strategy can introduce inefficiencies and risk. In a recent conversation with Ryon Packer, chief product officer at Motus, we discussed what’s driving the rise and why the usual mileage rate often falls short for reimbursing employees using personally owned vehicles.

What’s Driving the Recent Reimbursement Rate Increase?

The IRS calculates its standard mileage rate using national averages for vehicle ownership and operating costs, as outlined in its annual revenue procedure. Fuel prices are inclined to draw essentially the most attention, but they usually are not the first driver behind the rising rate.

“With fuel prices being managed downward, the undeniable fact that the reimbursement rate keeps going up shows you that every part else is getting that way more expensive,” Packer said.

Amongst the largest contributors:

- Maintenance and Repairs: Vehicle maintenance costs have risen by roughly 30%, driven by technician shortages and increasingly complex vehicle technology. “Nowadays, when you hit a pole, you’ve got parking sensors, proximity sensors, backup cameras, every part,” Packer said. “What was a ‘don’t worry about it’ repair is now hundreds of dollars.”

- Vehicle Acquisition Costs: Capital costs remain greater than 20% higher than pre-pandemic levels. While residual values are relatively strong, advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) and other embedded technology proceed to push up each purchase and repair costs.

- Insurance Premiums: Higher repair severity has translated directly into higher insurance premiums. “That then cascades into insurance,” Packer noted.

- Downtime and Rentals: Longer repair cycles mean increased reliance on rental vehicles, adding to overall operating costs.

Electric vehicles add further complexity, requiring specialized repair skills and, in some states, higher tax, title, and license fees to offset declining fuel tax revenue.

Why the IRS Rate Falls Short

A standard misconception is that employers are required to reimburse on the IRS rate. That just isn’t the case.

“There’s nothing within the IRS revenue procedure that claims you have to pay that,” Packer said. “What it says is that’s essentially the most you may claim tax-free.”

The speed itself is an “average of averages,” reflecting a national mix of car types, insurance costs, and operating expenses. As Packer put it, “The one thing a median guarantees you is that you’ll never hit the common.”

For a lot of fleet types, the mismatch is apparent. Pharmaceutical sales representatives are expected to project a certain image. Home healthcare staff drive compact vehicles, while construction or utility employees drive pickup trucks.

All of them face very different cost structures. Applying a single national average often ends in over-reimbursement for some employees and under-reimbursement for others.

Compounding the difficulty, lots of the reimbursement-related lawsuits making headlines are rooted in labor law, not tax compliance, Packer said. Using the IRS rate may offer administrative simplicity, nevertheless it doesn’t routinely address wage-and-hour requirements.

A More Targeted Option: Fixed and Variable Rate (FAVR)

The IRS allows three methods for substantiating vehicle reimbursements: actual costs, the usual mileage rate, and the Fixed and Variable Rate (FAVR) method.

Actual cost reimbursement requires collecting and auditing receipts, which most fleets find impractical. In contrast, FAVR allows organizations to define reimbursement based on role-specific requirements while remaining IRS-compliant.

“FAVR starts with asking, ‘What does the role require?’” Packer said.

Under a FAVR program, firms can specify vehicle type and trim level and even require certain safety technologies.

“We’re seeing more firms say, ‘We wish that vehicle, but we would like the tech package,'” Packer said, referring to ADAS technologies.

FAVR also supports stronger risk management by allowing employers to mandate higher insurance limits and a business-use rider, then reimburse employees for the added cost. These requirements help protect the organization while ensuring employees usually are not financially penalized.

The structure also can reduce liability exposure. In accordance with Packer, most accidents occur after business hours — between 5 p.m. and early morning on weekdays, and over weekends — when employees are using vehicles for private moderately than work purposes.

Reimbursement, Beyond a Single Model

While FAVR offers precision, it just isn’t the one alternative to the usual mileage rate. Some organizations use cents-per-mile reimbursement based on union-negotiated rates, which are sometimes lower than the IRS rate because they’re tailored to specific roles.

Others depend on allowances or hybrid programs, akin to reimbursing all vehicle costs except fuel, which could also be covered by an organization card for, say, utility staff whose vehicles idle for prolonged periods.

Technology platforms now support these approaches with ongoing compliance and risk management tools, including motorized vehicle record monitoring, license verification, and driver training designed for business professionals moderately than industrial drivers.

For fleets navigating rising vehicle costs, the takeaway is that precision matters. Because the IRS mileage rate continues to climb, fleet managers may profit from stepping back and evaluating whether an “average” solution still suits their organization’s operational, financial, and risk profile.

This Article First Appeared At www.automotive-fleet.com