World famous filmmaker and Disney sellout billionaire George Lucas got here of age mixed into the road racing scene of Modesto, California within the speed-addled Sixties. Shortly after he graduated highschool in 1962 with dreams of becoming an expert racing driver, he was forced to shelve his dream as a consequence of an incredibly serious accident. Resigned to a life doing something apart from racing, Lucas decided to attend USC film school to follow his second passion, directing and shooting filmstock. His first major project, a brief 8-minute tone poem film called “1:42.08 to Qualify,” followed famed racer Peter Brock in a borrowed Lotus 23 sports automotive, attempting to qualify for a race at Willow Springs. I contend that this short film is maybe crucial keystone piece of labor in cinema history.

Lucas and his tiny 14-person crew slept on the track during production and made the beautifully weird short film on an absolute shoestring of a budget. Not only did the film employ cameras mounted on the Lotus, but oftentimes Lucas himself would sit within the automotive next to Peter Brock to film his gearchanges or the swing of his tachometer. The living embodiment of speed is continuously felt within the dialogue-free sequences of tracking shots, car-to-car filming, and nose-cone mounted angles which might be still employed in automotive filmography today, in addition to innumerable hundreds of YouTube videos. Even in his early 20s, Lucas was a master of practical filmmaking. In response to Brock’s recounting of the time, Lucas already had ideas in his head for a series of science-fiction space westerns, “It sounded type of like Buck Rogers with unfamiliar beings and higher weapons. Very strange and we just type of nodded and patronized this enthusiastic kid.”

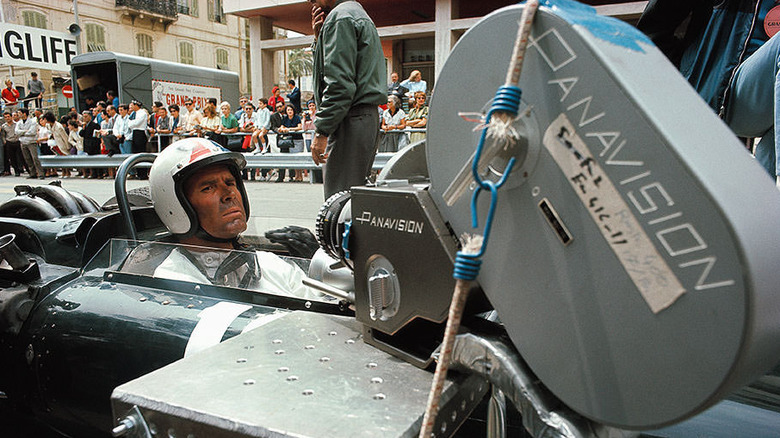

Only a month after his class film debuted, Lucas was on a plane over to Monaco to assist shoot John Frankenheimer’s motorsport magnum opus, “Grand Prix.”

‘Grand Prix’ influencing Lucas

We have talked about how great and influential “Grand Prix” is previously. The film completely modified how cinematography works, largely using lots of the same shot techniques Lucas had already adopted in his student project, inspired by the likes of David Lean, John Ford, Sergio Leone, and Akira Kurosawa. In response to Dale Pollock’s Skywalking, a biography of Lucas and his movies, the filmmaker’s time on the set of “Grand Prix” was eye opening.

“The studio forged and crew retired to portable dressing trailers at the top of a day’s shooting, while Lucas and company headed for his or her portable sleeping bags.” Lucas obviously admired Frankenheimer as a director and Saul Bass’ visual tour de force, the young would-be cinema icon was turned off the film’s 120-person crew and what he called Hollywood’s irreparable engine of waste. It was this waste that inspired Lucas to work with pared back crews even when developing an enormous space epic like the unique 1977 “Star Wars,” which reportedly used lower than half the crew that “Grand Prix” required only a decade before.

Lucas’ first two industrial movies, “THX 1138” in 1971 and “American Graffiti” in 1973 were produced with tiny sub-million dollar budgets and kept the reduced crew sizes that he was obsessive about shrinking. By the point he got to Star Wars and realized the extent of effects needed to create his vision, Lucas began Industrial Light & Magic to further reduce the variety of crewmembers needed to provide a scene. With visual effects now in his bag of cinematic tricks, George could conjure any massive scene from miniatures or set a scene entirely in a small backlot constructing.

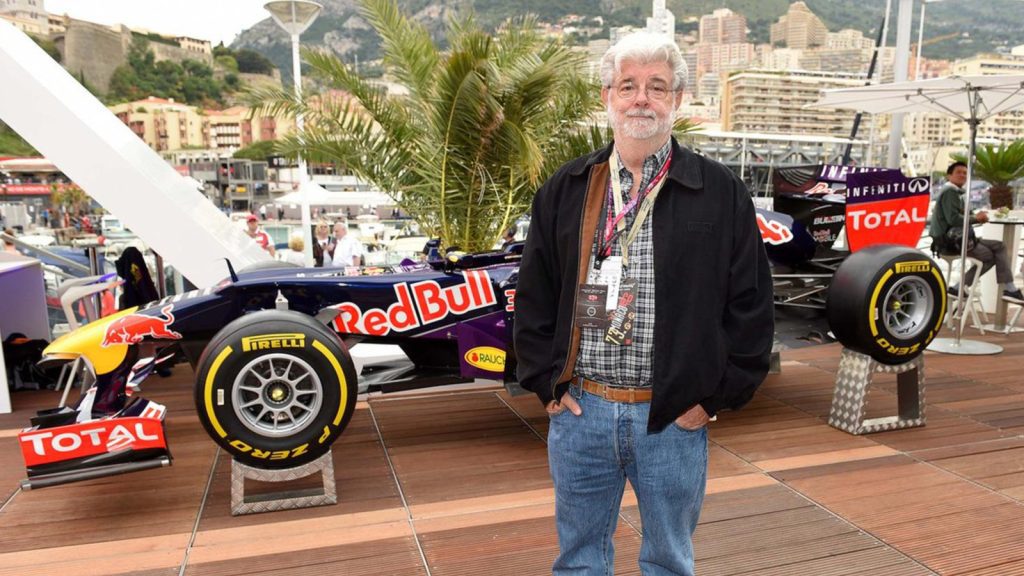

Today

“Grand Prix” reportedly cost $89 million adjusted for inflation to provide, while the comparatively grandiose “Star Wars: Episode IV – A Recent Hope” cost just $58.5 million adjusted for inflation. Each were incredibly successful movies with the previous proving itself perhaps the best racing film of all time, while the latter spawned a trillion-dollar global empire.

Lucas opened the floodgates of artificial effects with “Star Wars,” changing the face of moviemaking and setting the world up for the whole computer-generated movie atmosphere we experience today. Possibly you think that Lucas is chargeable for the downfall of Hollywood, or perhaps you possibly can appreciate that some stories are unattainable to inform without assistance from computer generated graphics, but in either case it’s obvious that George Lucas could be probably the most influential movie man in history. And it’s all due to cars and his time working on “Grand Prix.”

This Article First Appeared At www.jalopnik.com