Formula 1 is understood for its quirky methods in relation to aerodynamics and engineering. In that blend, brakes turn out to be an important component for the teams because stopping power is just as vital as raw horsepower in Formula 1. Irrespective of how briskly the newest Red Bull, Mercedes, or Ferrari goes, it has to decelerate just as effectively, often from over 200 mph to a crawl in a second and pulling 5Gs in the method. That is where Brembo is available in. The Italian brake giant has been a fixture in F1 since 1975, and today, all of the cars on the grid run Brembo braking technology in a single form or one other. Nevertheless, no two teams run the exact same system.

Each team’s brakes are custom-tailored to their setup, their drivers, and the circuits they’re racing on a given weekend. Which means one team’s Brembo setup might look very different from one other’s, even in the event that they share the identical basic DNA. And once you realize how critical brakes are in F1 — they’ll determine a position change and even influence races that may be won or lost under braking — you begin to grasp why this behind-the-scenes engineering war matters just as much as engine performance.

The science of carbon-carbon rotors

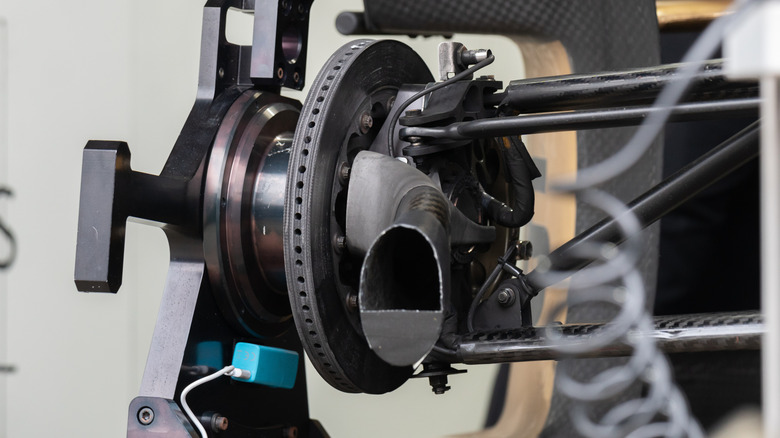

To delve deeper into Brembo’s braking tech in F1, we’ll have to have a look at the components that make up the system. At the center of each F1 brake system are the rotors, and things begin to get exotic right about here. Forget the steel or forged iron discs you see on road cars. F1 uses carbon-carbon composite rotors that are ultra-light, heat-resistant discs that may handle temperatures soaring above 1,832 Fahrenheit without warping or fading. This material is not carbon-ceramic, such as you’d find on high-performance cars, where a carbon fiber reinforces a ceramic core while the friction surfaces are also coated with a ceramic layer. It’s F1, in any case, so the fabric is much more specialized.

At Brembo, the carbon-carbon discs for F1 is a pure type of carbon that is featherlight, at around 50% lighter than standard materials. At racing temperatures it offers nearly double the grip, with a friction coefficient peaking at 0.6 in comparison with 0.3 for iron. Making these discs, nevertheless, is a painstaking four-month-long process that involves weaving sheets of carbon fiber into layers which can be then stitched by a needler machine. The raw carbon disc then goes through multiple carbonization baking cycles at as much as 4,532 degrees Fahrenheit. Once hardened, the rotors are precision-drilled so as to add a whole lot of cooling holes.

Performance comes at a price, though. Carbon brakes only bite properly once above 752 degrees Fahrenheit and peak beyond 1,202 degrees Fahrenheit, but at those temperatures, they face aggressive oxidation. This effectively burns away the surface, especially as braking temps spike to 2,192 degrees Fahrenheit. Even the air cooling them paradoxically accelerates that wear by feeding oxygen right into the discs.

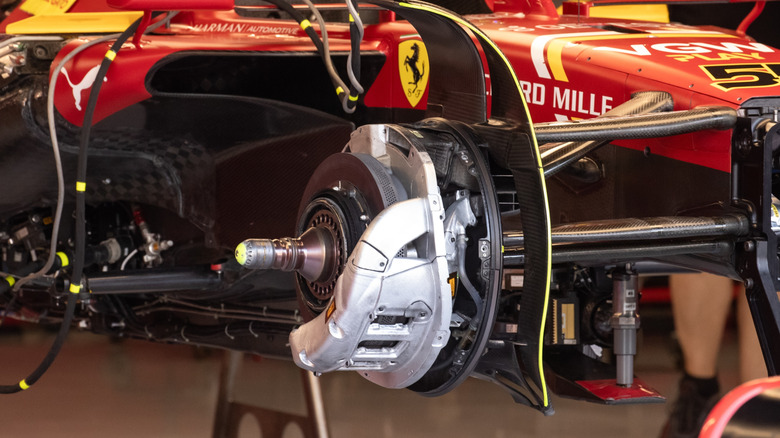

Calipers are bespoke engineered for each team

The rotor tech is pretty consistent across the teams. Brembo supplies the brake calipers too, but things diverge here on. The calipers are machined from solid billet aluminum for max strength and minimal weight of around five to six kilos. While the raw materials and manufacturing techniques are consistent, each team gets a custom solution for the caliper design in keeping with their requirements of stiffness and weight.

Brembo works with the teams individually, since calipers must integrate seamlessly with each chassis and suspension design. Some squads go for calipers that sacrifice rigidity in favor of weight savings, while others prioritize strength. Even the mounting points vary, which implies a caliper designed for one team is useless to a different. Regulations cap calipers at six pistons, but not every team uses the utmost all over the place.

The front axle almost at all times runs six pistons for max stopping force, while some teams run just 4 pistons on the rear to avoid wasting weight and simplify packaging. Cost-saving rules also limit each team to a single-spec front and rear caliper design per season. Which means the identical components must handle the heavy braking zones of Monza in addition to the stop-start nature of Monaco, forcing teams to optimize their overall balance slightly than tailor calipers race by race.

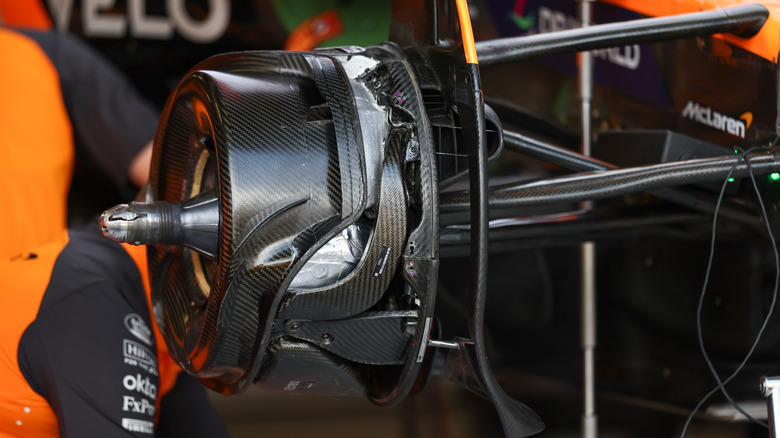

The hidden aero trickery which can be brake ducts

If calipers are the muscle of the braking system, imagine brake ducts because the lungs. They channel cooling air directly onto the discs and calipers, stopping overheating; but in F1, nothing is ever easy. Brake ducts don’t just cool the brakes, they’re also playing a double-role as a key piece of aerodynamic strategy. Every team designs its own ducts to balance brake cooling with downforce generation, and ultimately affecting tire performance, too. The FIA tightly regulates their size and placement, but inside those limits, ducts can double as aerodynamic devices, shaping airflow across the wheels and into the diffuser. A poorly designed brake duct may cause drag and overheating. A well-designed one gives the automobile stable brakes and a cleaner aero profile.

Brakes work by converting kinetic energy into heat through friction, but they’re only glad in a narrow temperature window: too hot and oxidation chews them away, too cold, and so they simply don’t bite. Cooling management is every part, and teams do it with ducting across the calipers, and directly into the discs and pads. The scale of those ducts varies wildly depending on the braking requirements.

Teams run larger air ducts for tracks that need heavy braking, sacrificing around 1.5% aerodynamic efficiency. Brembo has pushed design further with discs drilled with as much as 1,000 tiny ventilation holes, modeled via CFD to maximise airflow and thermal discharge without compromising strength. Brake cooling is essential enough a subject to warrant, considering drilled and slotted rotors in your regular road automobile as well.

Brake pad materials are the key sauce

Unlike the ceramic, semi-metallic or organic brake pads you’d find on a road automobile, F1 pads use a carbon-based friction material called CER, developed to handle the form of punishment only an F1 race can deliver. We’re talking about peak operating temperatures brushing 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit, with the power to warm up rapidly and reach peak efficiency inside moments of use.

That quick warm-up is critical as drivers need immediate confidence in braking from the very first corner, not a lap later. What makes these pads truly special is their ability to mix extreme heat tolerance with low wear and predictable response. Which means the brake pedal feels rock-solid from lights out to the checkered flag, giving drivers precise modulation through every braking zone.

Thermal conductivity is one other secret weapon, allowing pads to spread and shed heat more effectively while resisting the dreaded fade. Nevertheless, these pads aren’t invincible, as heat-soak during long pit stops can push temps over 2,192 degrees Fahrenheit, sometimes setting brakes alight. And while they’re tough, they do not last long, just 550 miles before they’re toast. Over a season, Brembo supplies each two-car team with as much as 480 pads, proving just how consumable this element of the braking system really is.

The attention-watering cost of F1 brakes

Brembo upgrades for normal cars may be considered exotic, which can be one other solution to assume that they are expensive; and so they are. So it’s only natural for F1 tech to be on an astronomically high cost level as compared. A single carbon-carbon rotor for an F1 automobile can cost as much as $3,000, and every automobile needs 4 of them plus spares, and one set lasts two race weekends at best. Add in calipers at $5,600 each, master cylinders at $5,400 each, and the pads costing cheaper at $780 each. But that is just the principal elements of the braking system. The ducts, the supporting hardware and electronics, all demand high manufacturing costs, so you are looking at a grand total of $66,000 after which some. With two cars, a full season’s price of brake components alone, can run a team well into the tens of millions.

This level of expense is one reason F1 brakes remain off-limits to consumer cars. Even supercars with carbon-ceramic brakes operate in a completely different universe of performance and value, despite coming a good distance from the primary automobile with disc brakes and the tech used back then. Brembo does supply a few of that tech to road cars, however the carbon-carbon rotors in F1 remain racing-exclusive. For a team like Mercedes or Ferrari, brake costs are only one other line item within the nine-figure budget. For us mortals, it is a reminder of how far removed F1 tech really is from what’s on our driveways.

In the long run, the Brembo monopoly is solely about trust in a manufacturer that guarantees unsurpassable stopping power and safety, slightly than simply uniform technology support for the teams. Teams know that they cannot risk their race, cars, or their driver’s safety; there is no such thing as a query of alternative here. That is why, from the front of the pack to the backmarkers, you will find Brembo logos stamped on every brake caliper in Formula 1.

This Article First Appeared At www.jalopnik.com